Phase 0 Archaeological Study of Brandymore Castle, Arlington County, Virginia

by

Luke Burke

February 4, 2022

Brandymore Castle is a rock formation and historic landmark located in Madison Manor Park in Arlington County, VA. Nearby the rocks are two apparent man-made features – a trench and embankment – of unknown origin. The creation of bike trails throughout the park, and possible widening and realignment of bike trails bordering the park, could damage the rocks and other historical resources contained in the park. The purpose of this study was to provide an initial assessment of the man-made features in the park to ensure Arlington County and NOVA Parks plans account for protection of any historical resources. This information was collected via site survey of the project area and research into human occupation of the area to identify possible uses for the trench and embankment.

Research shows that Native Americans created a nearby soapstone workshop and both Confederate and Union Army forces occupied the area during the Civil War. Following the war, property owners operated a farm and quarry, and later built a house directly in the project area. Comparison of site survey photos, measurements, and Arlington County GIS maps to documentation of Civil War defenses show some similarities, however, a military historian familiar with the site believes that the trench and embankment do not conform to military designs. While Confederate and Union Army forces constructed earthworks around the Seven Corners area, approximately one mile from the project area, no documents positively identify earthworks at Brandymore Castle. Additionally, the research did not identify any documentation sufficient to rule out any prior occupants as the party responsible for the trench or embankment.

Further research is recommended in the form of a Phase I Archaeological Survey of the entire Brandymore Castle location to determine the significance of the site and identify archaeological resources from all prior occupants.

Table of Contents

Table of Figures

Figure 1. Map showing the project area in the red rectangle (Google Maps, n.d.) 1

Figure 4. West-facing photo of trench 3

Figure 5. Southwest-facing photo of trench taken from the trail crossing 4

Figure 6. Measurements of the Deepest Section of the Trench 5

Figure 7. Southeast-facing photo of embankment 6

Figure 8. West-facing photo of embankment 7

Figure 9: Remnants of the house at Brandymore Castle 7

Figure 10. Trail along the former driveway path 8

Figure 11: Fragments of a ceramic plate 8

Figure 12. 1865 Civil War map showing the project area, in red (Corbett) 10

Figure 13. Rebel works beyond Munsons Hill embrasured (Waud, 1861) 11

Figure 14. Rebel works at Mason’s Hill (La Brea et al., 1885) 11

Figure 15. 1865 Civil War map showing the project area in the red rectangle (Barnard) 13

Figure 16. Design of rifle trenches around forts (Cooling, Owen, 2010) 14

Figure 19. Comparison of Brandymore Trench and Embankment to Battery Heights. 16

Figure 20. 1878 map showing the Gott house, in the red circle, near the project area (Hopkins). 17

Figure 21. 1900 Map Showing Boundary of the Gott Property (Howell and Taylor). 17

Figure 22: Advertisement for the Gott Quarry (Evening Star, 1866) 18

Figure 24. Aerial View of House within the project area (Sanborn, 1936) 19

Figure 25. Aerial view of house within the project area (Fairfax GIS, 1937) 20

Figure 26 Aerial view of project area after demolition of the house, (Fairfax GIS, 1972) 20

Brandymore Castle is a rock formation located in Madison Manor Park in Arlington County, VA which is best known as a reference point for the boundaries of several 18th century land grants (Moxham, 1973). The park also includes two features, a trench and embankment, which appear to be man-made. Prior to establishment of the park historical occupation in the area included a Native American soapstone workshop, Civil War military outpost, farm, post-Civil War quarry, and residential development. Recently, park users created bike trails on the hill which could damage the rocks and any other historical resources onsite (Clark, 2020). The proposed NOVA Parks Washington & Old Dominion (W&OD) Trail widening project might also affect the park’s historical resources. The purpose of this study was to provide an initial assessment of the man-made features in the park to ensure Arlington County and NOVA Parks plans account for protection of any historical resources.

The study consisted of a site survey of the trench and embankment, and research into human occupation of the area to identify possible uses for these features. The trench and embankment could relate to road, rail, trail, or utility construction. A limited amount of research was done to investigate these possibilities without identifying meaningful results. A more exhaustive search of the possible resources related to these uses was time-prohibitive and considered out of scope for this study.

The project area consists of the land surrounding Brandymore Castle, as shown in the red-dotted rectangle in Figure 1. Approximate locations for the trench and embankment are represented by the white line and red map marker, respectively.

Figure 1. Map showing the project area in the red rectangle (Google Maps, n.d.)

The north side of the project site is adjacent to the W&OD Trail, which runs along the former path of the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire (AL&H) Railroad. Beyond the trail are Interstate-66 and metro tracks. The west side of the project area is bounded by a portion of the trail and Roosevelt Street. A residential neighborhood and parkland adjoin the south and east sides, respectively.

Figure 2 shows the project area in relation to Madison Manor Park.

Figure 2. Map showing Madison Manor Park and project area in the red rectangle (Arlington County GIS Website, 2022)

Tasks included checking Arlington County’s site inventory for the presence of known archaeological sites, checking historic maps and other documentary sources for indications of historic occupation, and visually inspecting the proposed project area by pedestrian survey to document observable surface features.

Visual inspection of the project area consisted of pedestrian surveys conducted between September 2019 and April 2021. The GIS map in Figure 3 shows the key terrain features located in the project area.

Figure 3. GIS map view of Brandymore Castle at Madison Manor Park, Arlington, VA. (Arlington County GIS Website, 2022)

It was difficult to physically measure the length of the trench due to the substantial number of fallen branches and undergrowth in the trench. Following the surveys, the trench length was calculating using the Google Maps aerial view and measuring tool to arrive at a rough estimate of length of 225 feet.

Figure 4. West-facing photo of trench

The depth of the trench is not uniform along its entire length. The trench flattens out on each end, and a filled-in dirt trail crosses the trench near the middle as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Southwest-facing photo of trench taken from the trail crossing

The estimated slope on each side of the trench at the deepest section is 45 degrees. Measurements of this section were taken with a tape measure. Figure 6 shows the measurements on top of a profile photo of the trench.

Figure 6. Measurements of the Deepest Section of the Trench

The embankment is approximately 135 feet from the top of the trench. The boundaries of this feature were difficult to distinguish, and no suitable measurements were taken.

Figure 7. Southeast-facing photo of embankment

Figure 8. West-facing photo of embankment

Remnants of the house, shown in Figure 9, still exist at southern end of the project area near the embankment.

Figure 9: Remnants of the house at Brandymore Castle

Trails run throughout the park, including one that curves in front of the embankment where the house’s driveway was previously located.

Figure 10. Trail along the former driveway path

Ceramic sherds, glass fragments, bricks, and asphalt fragments cover the hillside, most of which is related to residential and recreational use. Figure 11 below shows fragments of a ceramic saucer found on the trail.

Figure 11: Fragments of a ceramic plate

Arlington County designated Brandymore Castle a local historic district on May 17, 1986 and designated the highest portion of the site a historic landmark. The landmark designation form submitted to the Arlington County Board for approval only references the location’s importance as a locating point in 18th century land grants in its description of the site (Arlington Historical Affairs and Landmark Review Board, 1986). The Phase XI Architectural Survey Report of Arlington County, Virginia completed in July 2009 recommended the Brandymore Castle site for a Phase I Archaeological Survey (Traceries, 2009) but no survey has been conducted to date. A recent column in the Falls Church News Press (Clark, 2020) is the only published material identified that specifically mentions the trench and embankment. A military historian with experience surveying Civil War defenses visited the site several times in 2008 and their input was collected via email.

Several resources were used to examine the land use history of the project area. Sources included, but were not limited to historic maps, historic aerial photographs, Civil War correspondence, newspapers, and local historical publications. Particularly useful for this project were the historical maps and correspondence from the Library of Congress as well as historic aerial photographs and maps from the Fairfax and Arlington County GIS websites. The following paragraphs summarize the results of the research.

Northern Virginia was first populated by Native Americans and evidence of a Native American soapstone workshop near the project area is described in the excerpt below from an 1889 symposium:

“At a point one mile below Falls Church, Virginia, on the old Febrey estate, I found a small but interesting soapstone workshop. It is located on a hillside overlooking Four-Mile Run and about one-fourth of a mile below a recently worked soapstone quarry. Large pieces of the unworked stone and fragments of unfinished vessels covered the ground, which occupies an area of not more than half an acre in extent. No perfect vessels were found, and the best specimen obtained was a small core worked out from the interior of a vessel in the process of its construction. Several quartz implements suited for working the stone were found mingled with the debris. The amount of material on the ground was comparatively small, when compared with that at the Rose Hill quarry, and probably it had been carried from the quarry above, where the recent operations have obliterated all traces of ancient mining, if any existed. Careful and repeated search in the neighborhood of this quarry only resulted in the discovery of a few pieces of unfinished vessels-enough, perhaps, to justify the conclusion that this quarry furnished the material used at the workshop.” (Proudfit, 1889)

The Febrey property referred to could be that of Henry, Nicholas, or John Febrey. As seen in the 1865 map in Figure 15 each of these Febreys owned land below Brandymore Castle in relation to its position along Four Mile Run. The “quarry above” may refer to Richard Gott’s quarry at Brandymore Castle.

Proudfit also mentions a village site “on the farm of Isaac Crossmun, at Falls Church, Virginia.” Proudfit clarifies that his use of the term village site “is not to be understood as signifying a place formerly occupied by a compact group of dwellings, but rather one where their proximity to each other was interrupted by considerable spaces devoted to agricultural and other purposes.” (Proudfit, 1889). Assuming the site Proudfit surveyed is Brandymore Castle, if the trench was present at the time, he did not consider it to be related to a Native American quarry or village site.

Residents in the area have found Civil War-era minie balls at the park and wondered if the trench and embankment also date to the Civil War (Clark, 2020). During the Civil War “much of the northern Virginia countryside was dotted with small picket posts, camps, and other strong points designed to offer an early warning net for the Defenses of Washington.” (Cooling, Owen, 2010) Maps and correspondence document the presence of troops and defensive structures from both the Union and Confederate Armies throughout the region.

The Confederate Army established outposts at Mason’s, Munson’s, and Upton’s Hills in August 1861. Virgil P. Corbett, a civilian who resided in the area in 1861, created the map in Figure 12. Corbett “went so close to the rebel works that he was discovered and chased by the rebels” (New York Times, 9/17/1861).

Figure 12. 1865 Civil War map showing the project area, in red (Corbett)

After Union soldiers occupied the positions in late September 1861 Northern newspaper correspondents provided detailed descriptions of Confederate works around the area.

“The “fort” on Munson’s Hill I find to be perhaps 300 yards long, in the circuit of its parapet, the whole being nothing more than infantry breastworks, having, however, a rather formidable “Quaker” gun, in the shape of an ash log with a dab of black paint at the butt to represent the muzzle. Such other and more valuable guns as they may have had here, had been carefully removed by the Confeds when they withdrew their pickets previously. At the earthwork to the rear of Munson’s Hill, the retreating Confederates had left six sections of stove pipe mounted in the six embrasures; and some rather formidable-looking (at a distance) earthworks upon Mason’s Hill proved, on the occupation of that point by our troops, to be just about of the same bogus nature.” (Evening Star, 9/30/1861)

The Confederate earthwork to the rear of Munson’s Hill, located on Perkins’ Hill near Seven Corners, is illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Rebel works beyond Munsons Hill embrasured (Waud, 1861)

A Confederate rifle trench on Mason’s Hill is illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Rebel works at Mason’s Hill (La Brea et al., 1885)

Another Northern correspondent provided a description of encampments and earthworks at nearby Upton’s Hill.

“The first signs of the encampments recently occupied by the rebels on the road from the Georgetown Aqueduct are found just this side of Ball’s Cross Roads, consisting of rails set up and covered with straw, and of brush huts sheltered by thick overhanging cedar and pine. A few rods east of Upton’s Hill there are quite a number of these rail huts, covered with corn fodder and rye straw, capable of accommodating about one regiment. A ridiculous specimen of Confederate earthworks, consisting of a little ridge of dirt, thrown up about two feet high, runs along the side of Upton’s Hill—the only signs of rebel fortifications in that vicinity.” (Evening Star, 10/4/1861)

A Confederate correspondent from the 18th Virginia Regiment specifically mentions picket duty at Brandymore Castle as well as an incident involving Confederate and Union artillery.

“A Trip on Picket – View of Washington.

Correspondence of the Richmond Dispatch

Near Fairfax Court-House,

Sept. 12, 1861

On Friday, the 5th of this month, our regiment was ordered to leave its encampment near Fairfax Court-House, and go up towards Washington on picket duty…

After stopping to rest several times and filling up our canteens with good cool water, we came in sight of Falls Church, distant about ten miles from our encampment. This is a neat village containing about twelve families and four churches, at one of which it is said that General Washington often attended service. The boundary line of the original District of Columbia runs just beyond Falls Church. After passing the line stones of this District, now called the County of Alexandria, we marched about three quarters of a mile and stretched our arms upon Brandymore Castle, near the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire railroad…

While we were looking over at the enemy, and lying carelessly about our posts, some six or eight cannon balls came over our heads and took us by surprise. Col. Withers gallantly came to our assistance with the balance of the regiment and a display of artillery, as if for battle, whereupon they kept remarkably quiet the rest of the day.” (Daily Dispatch, 9/17/1861)

A soldier from the 9th South Carolina Regiment also describes picket duty at Brandymore Castle.

“Virginia Correspondence

[For The Lancaster Ledger.]

Brandy-more Castle Hill, Sep. 19.

From the caption, it might be inferred that our camp and quarters have been located in some place of celebrity, with every convenience, comfort, and strength, strongly fortified, and “all that.” Such was true of Castles in olden times – such might be supposed true of this, but beyond the name it is not so. It is true, that it is a hill, with rocks just as nature arranged them, with a running stream at the foot. It is among the many romantic hills included in the original grant of Land to Lord Fairfax. In subsequent conveyances, the name has been preserved. The present inhabitants may tax every ingenuity in vain to discover a fitness, an appropriateness between the place and the name – Brandy-more Castle Hill. Those who named it no doubt saw the aptness, the becomingness of the appellation, but the reason has not been left on record and the light of nature now does not enable me to discover it; however, it is immaterial.

The present occupants are the members of the 9th Regiment. We found no Castle, house, or other shelter or covering upon it, and we will leave it in the same situation. It is about seven miles from Alexandria on the Rail Road from that city to Leesburgh – about six miles in an air line to Washington – nearly two miles east of Falls Church – about two mile north of Munson’s Hill and one mile from Upton Hill, and about the same or probably a little further from Hall’s.” (Lancaster Ledger, 10/9/1861)

While the Confederate forces and defensive works were not significant in strength the research illustrates the proximity of Confederate earthworks to the project area. Trenches like those constructed at Mason’s and Upton’s are smaller in scale than the Brandymore Castle trench but the earthworks at Perkins’ Hill are comparable to the Brandymore Castle embankment.

Following the Confederate withdrawal, the Union army advanced and set up large camps throughout the region, including at Upton’s, Minor’s, and Hall’s Hills. Union troops constructed Forts Ramsay, Buffalo, Taylor, and Munson in the Seven Corners area as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15. 1865 Civil War map showing the project area in the red rectangle (Barnard)

A soldier from the 21st New York Regiment describes the earthworks in the area in a letter written October 19, 1861.

“On Upton’s Hill a strong fortification has been erected, mounting about a dozen guns, which will sweep the country in about every direction, being on the highest point of grounds there is in the vicinity. Besides the fort there are two batteries with embrasures for six guns on other portions of the hill, that will sweep the railroad track and the valley through which it runs.

About a half mile west of the Fort on Upton’s Hill, is the fortification upon which our regiment, assisted by detachments from the 23d and 35th New York Regiments, have been at work. It was commenced two weeks ago yesterday morning, and is now nearly finished. The trenches and parapet may be said to be finished and the stockade nearly so. It has embrasures for seven guns. Its general shape is that of a semi-circle, the parapet describing the half-circle and the parapet the diameter. Its guns will sweep in every direction save in an easterly one.” (Buffalo Daily Courier, 10/24/1861)

A soldier in the 23rd New York Regiment wrote a similar description of works in the area on October 23, 1861.

“This and the Twenty-First regiment have finished their labors on two small pentagonal earth works a short distance in front, which will mount seven guns each, and the cannon are also mounted in the fort at Upton’s House, so we consider our digging duties finished in this immediate neighborhood. We have also erected two field breastworks here for the use of the light battery at our left elbow in case they might be needed for the protection of the cannoniers.” (Elmira Weekly Advertiser, 11/2/1861)

Although the descriptions are similar, they do not offer enough detail to locate the field batteries. Besides his reference to Fort Ramsay on Upton’s, the 21st NY soldier writes of a semi-circular fort which appears to describe Fort Buffalo. It is not clear if the two batteries refer only to Fort Taylor, which would have covered the railroad and valley, or if there is an additional battery not shown on the map. The reference is probably not to the works at Perkins’ and Munson’s Hills as neither would cover the tracks and valley through which it runs.

The Brandymore Castle trench is roughly similar in scale to the design for rifle trenches around forts in the defenses of Washington, shown in Figure 16. The depth and width of the Brandymore Castle trench are 4.5 ft. and 6 ft. respectively, although the front slope of the Brandymore Castle trench is not as steep.

Figure 16. Design of rifle trenches around forts (Cooling, Owen, 2010)

A 2001 archaeological survey of Battery Heights in Alexandria, VA studied the remains of an unmanned battery and rifle trench. Figure 17 is an excerpt of the survey’s site map which shows the trench and battery. The placement of a trench in front of an embankment is similar to the Brandymore Castle site, although the Battery Heights trench is 30-40 ft. from the battery which is much closer than the distance between the Brandymore Castle trench and embankment.

Figure 17. Location of earthworks on Battery Heights, Alexandria, VA (John Milner Associates, Inc, 2001.)

The profile drawing of Battery Heights in Figure 18 shows how the trench is located on lower ground in front of the battery.

Figure 18. Profile of Earthworks on Battery Heights, Alexandria, VA (John Milner Associates, Inc, 2001.)

The Brandymore Castle trench is also located on lower ground in front on the embankment. A side-by-side comparison of the Brandymore Castle features to those at Battery Heights demonstrates the similarities between the two locations.

Figure 19. Comparison of Brandymore Trench and Embankment to Battery Heights.

While there are similarities between the Brandymore Castle site and Civil War earthworks the differences in the slope and positioning cannot be overlooked. A military historian examined both the trench and embankment during visits to the site in 2008. They determined that the trench does not confirm to a military layout. In addition, the embankment is not oriented in a military manner and depressions in the embankment appear to be more consistent with tree root wads or post-war activities.

Documentation of farm use on the property dates to the mid-19th century. Major Richard Gott built a hunting lodge on the site prior to the Civil War.

“While living in D.C., Major Gott built a hunting lodge near Falls Church on land his wife had inherited from her father, William Gordon-other sisters and brothers had inherited land near the now Army-Navy Country Club and on Arlington Ridge Road- the Slaymakers and Heiners. This lodge became his home after the War Between the States” (Gott, p.24)

“After the surrender, Dr. Gott returned to Falls Church, where he began general practice. His father, who had served throughout the war in the Confederacy also returned to his home, Buena Vista, formerly his hunting lodge, to begin farming. Major Gott soon turned the farm over to his son, Dr. Gott.” (Gott, p. 26)

More recent research suggests Gott built a new home at the site after the war.

“The oldest, extant house in the neighborhood was constructed by the Gott family at what is now 1301 North Roosevelt Street (000-4211-0097). Known as Buena Vista, the house was constructed ca. 1867-1868 for Richard Gott, a veteran of the Civil War. The 130-acre property served as the trucking farm of Dr. Louis Edward Gott, a surgeon for the Confederate army.” (Traceries, p. 46)

The 1878 map in Figure 20 shows the proximity of the Gott home to the project site.

Figure 20. 1878 map showing the Gott house, in the red circle, near the project area (Hopkins).

The map in Figure 21 shows boundaries of the Gott property in 1900.

Figure 21. 1900 Map Showing Boundary of the Gott Property (Howell and Taylor).

Farmers commonly use irrigation and drainage ditches but the location of the trench in between bends of Four Mile Run and adjoining rocky terrain indicate that it is unlikely this trench was used as such.

Richard Gott published an advertisement for a quarry along the AL&H Railroad in the February 19, 1866, Evening Star, shown in Figure 22.

Figure 22: Advertisement for the Gott Quarry (Evening Star, 1866)

In the 1970s Robert Moxham observed evidence of a quarry at Brandymore Castle, finding that “the north side of the hill has been quarried to a small extent but the craggy masses at the summit are essentially undisturbed.” (Moxham, p. 9).

Figure 23 is a portion of the GIS Map view centered on the rocks at Brandymore which shows a long depression running along a straight line.

Figure 23. GIS map view of the rock formation at Brandymore Castle (Arlington County GIS Website, 2022)

Photos were taken of the rocks during the site survey but trees and undergrowth at the site made it difficult to confirm if the depression is the quarry site. Given the proximity to the likely quarry site, it is possible that quarry operators dug the trench, but the site survey did not identify any superficial evidence to support or refute a relationship.

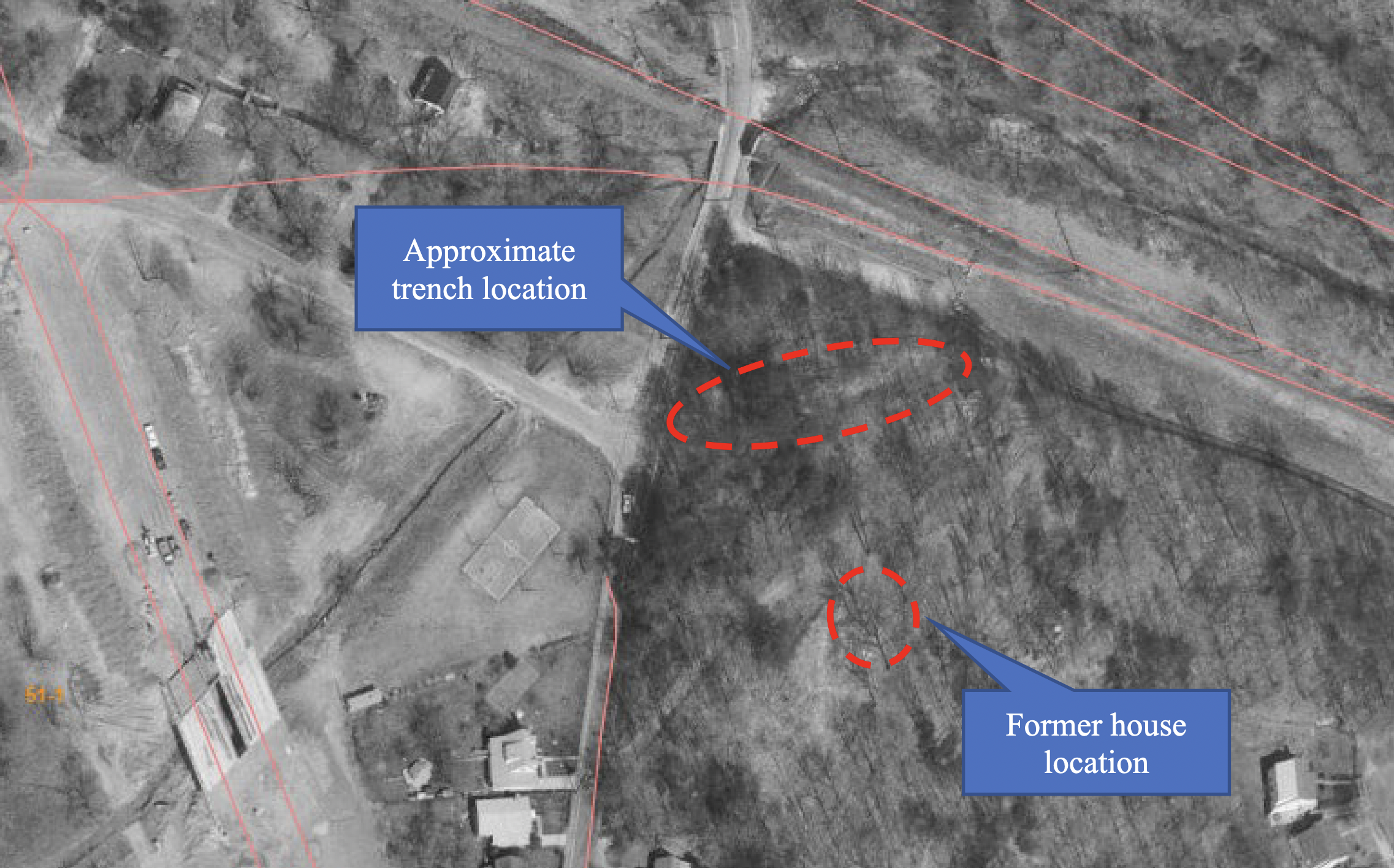

No house is present in the project area on Civil War maps or the 1878 map. Figure 24, a 1936 map of the area, shows a house at Brandymore Castle as shown in the red-dotted circle.

Figure 24. Aerial View of House within the project area (Sanborn, 1936)

The house, driveway, and possible garden area can be seen in aerial photos dating back to the 1930s, as shown in Figure 25. The red-dotted oval shows the approximate location of the trench.

Figure 25. Aerial view of house within the project area (Fairfax GIS, 1937)

Arlington County demolished the house sometime after acquiring the property for parkland in the 1960s. The 1972 aerial photo in Figure 26 shows the area after demolition.

Figure 26 Aerial view of project area after demolition of the house, (Fairfax GIS, 1972)

Park visitors can still see remnants of the house in the southern end of the project area near the embankment. Neighborhood residents have learned that the location was also used as a dumping ground, which, combined with nearly five decades of recreational use, explain the large volume of debris found throughout the park.

The trench and embankment at Brandymore Castle bear some resemblance to Civil War earthworks but there is no documentation that positively identifies earthworks at the project site. Numerous Confederate works are noted elsewhere in the area and soldiers’ correspondence provides documentation that Confederate units camped at Brandymore Castle. A battery on the hill could have provided defense against Union forces advancing up the road now known as Roosevelt Street.

If the features are Civil War-related, then Union Army construction of earthworks at the site appears to be more plausible. The arrangement of the trench and embankment features at Brandymore Castle are similar to Union earthworks documented on Battery Heights in Alexandria. The project area is located between Seven Corners and Minor’s Hill, being approximately one mile from both. Given the north-west orientation of the trench and location of the embankment on the western side of the hill a battery at Brandymore Castle would have provided defense between Seven Corners and Minor’s Hill against Confederate forces advancing along the railroad.

A military historian who visited the site several times believes the similarities are coincidental. While documentation shows Civil War activity at the site, there are no records of fortifications, or more than temporary occupation and the trench and embankment do not conform to a military layout.

Documentation reviewed during this study does not provide enough detail to rule out Native American, farm, quarry, and residential users of the area as creators of the trench and embankment. The proximity of the trench to the embankment could also be a coincidence and different users could be responsible for each. Grading for the house construction could be responsible for the embankment while the trench, being adjacent to roads, rails, and trails for decades, was created as part of one of those construction projects. There is considerably more documentation on these topics which is focused on the Northern Virginia area. Another study will provide the opportunity to review more sources to identify possible uses not considered in this study.

Arlington County should expedite the completion of a Phase I Archeological Survey, so the information is available before approving any changes to the park. Brandymore Castle was already recommended for a Phase I survey in 2009, and the information gathered during this study reinforces the need to conduct a follow-on survey. While this site survey and research suggest the trench and embankment could be Civil War earthworks, a 2008 survey determined it is more likely that the features were added in the 20th century, and there are countless other possibilities which cannot be ruled out. Measurements should be taken with precision instruments and physical evidence should be collected through metal-detecting and shovel tests. Analysis of artifacts and soil found through sub-surface excavation will enable researchers to determine the creator and purpose of the earthworks with a greater degree of confidence.

A Phase I study will also provide the opportunity to examine the entire Brandymore Castle area for presence of artifacts from all prior occupants. Surveys at Rock Creek Park (Louis Berger Group, 2008) and Barkhamsted’s Peoples State Forest (Hartford Courant, 2015) demonstrate the value in re-examining previously studied Native American sites. Archaeologists will have access to modern techniques not available to prior researchers, which may bring new discoveries to light.

Moxham, Robert H. “The Re-Discovery of Brandymore Castle”, Arlington Historical Society Magazine, Vol. 5, No. 1, October 1973, p. 3. http://arlingtonhistoricalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/1973-2-Brandymore.pdf

---. “The Re-Discovery of Brandymore Castle”, Arlington Historical Society Magazine, Vol. 5, No. 1, October 1973, p. 9.

Google. (n.d.). [Google maps satellite image of the area around Brandymore Castle]. Accessed 2020. https://www.google.com/maps/@38.882989,-77.1479241,1540m/data=!3m1!1e3

Arlington County GIS. Historic Aerial Photographs. Arlington County Government, Arlington, Virginia. Accessed January 12, 2022. https://gis.arlingtonva.us/gallery/map.html?webmap=28ea281cba6a4a5a8050df04c7fbb478

Arlington Historical Affairs and Landmark Review Board. Historic Landmark Designation for “Brandymore Castle”, April 23, 1986. https://arlingtonva.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2019/03/Designation-CB-report_1986.pdf

E.H.T. Traceries, Inc. Eleventh Phase of an Architectural Survey in Arlington County, Virginia, July 2009, p. 157. Prepared for Arlington County, Virginia, Department of Community Planning, Housing and Development. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/pdf_files/SpecialCollections/AR-069_11th_Phase_AH_Survey_Arlington_2009_TRACERIES_report.pdf

---. Eleventh Phase of an Architectural Survey in Arlington County, Virginia, July 2009, p. 46. Prepared for Arlington County, Virginia, Department of Community Planning, Housing and Development.

Clark, Charlie. Our Man in Arlington, Falls Church News Press, October 9, 2020.

https://www.fcnp.com/2020/10/09/our-man-in-arlington-397/

Proudfit, S.V. “Ancient Village Sites and Aboriginal Workshops in the District of Columbia.”, The Aborigines of the District of Columbia and the Lower Potomac - A Symposium, Under the Direction of the Vice President of Section D. The American Anthropologies, July 1889, p. 245. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1525/aa.1889.2.3.02a00020

The New York Times, New York, NY, September 17, 1861. Boston Rare Maps: accessed January 11, 2022. Link

Corbett, V. P., Cartographer, Publisher, and Millard Fillmore. Map of the seat of war showing the battles of July 18th, 21st & Oct. 21st. [Washington: Published by V.P. Corbett, 1861] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/99439216/

The Evening Star, Washington, D.C. September 30, 1861, p. 2. Thomas Tryniski, Old Fulton New York Post Cards, http://www.fultonhistory.com : accessed January 10, 2022. Link

Waud, Alfred R., Artist. Rebel works beyond Munsons Hill embrasured. United States Munson's Hill Virginia, 1861. [ca. September 28] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2004660307/

La Brea, Benjamin; Beath, Robert B.; Carrington, W.C.; Porter, David D.; Sheridan, Philip Henry. The Pictorial Battles of the Civil War. Sherman Publishing Company, 1885.

The Evening Star, Washington, D.C. October 4, 1861, p. 2. Thomas Tryniski, Old Fulton New York Post Cards, http://www.fultonhistory.com : accessed January 10, 2022. Link

The Daily Dispatch, Richmond, VA, September 17, 1861. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024738/1861-09-17/ed-1/seq-1/

The Lancaster Ledger, Lancaster, S.C., October 9, 1861, p. 2. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026900/1861-10-09/ed-1/seq-2/

Barnard, J. G, A Boschke, and United States Coast Survey. Map of the environs of Washington: compiled from Boschkes' map of the District of Columbia and from surveys of the U.S. Coast Survey showing the line of the defences of Washington as constructed during the war from to 1865 inclusive. [?, 1865] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/88690673/

Buffalo Daily Courier, Buffalo, NY, October 24, 1861. Thomas Tryniski, Old Fulton New York Post Cards, http://www.fultonhistory.com: accessed January 12, 2022.

Elmira Weekly Advertiser and Chemung County Republican, November 2, 1861, p. 3. NYS Historic Newspapers. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/lccn/sn85054482/1861-11-02/ed-1/seq-3/

Cooling, Benjamin Franklin III and Owen, Walton H. II. Mr. Lincoln’s Forts, p. 121, 2010.

---. Mr. Lincoln’s Forts, p. 32, 2010.

John Milner Associates, Inc. Results of Archaeological Survey Battery Heights, Alexandria, February 2001. Prepared for Carrhomes, Annandale, VA. https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/archaeology/SiteReportFiedel2001BatteryHeightsAX186.pdf

Gott, John Kenneth. Louis Edward Gott, M.D., The Arlington Historical Magazine, Vol. 3, No. 3, October 1967, p. 24. http://arlingtonhistoricalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/1967-5-Gott.pdf

---. Louis Edward Gott, M.D., The Arlington Historical Magazine, Vol. 3, No. 3, October 1967, p. 26.

Hopkins, Griffith Morgan. Jr. 1878 Atlas of Fifteen Miles around Washington, Including the Counties of Fairfax and Alexandria, Virginia/ Compiled and Published from Actual Surveys by G.M. Hopkins. G.M. Hopkins, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Electronic document. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1878_Alexandria_County_Virginia.jpg

Howell and Taylor, Map of Alexandria County, Virginia for the Virginia Title Co., The Virginia Title Company, Alexandria, VA.

Alexandria Gazette. Alexandria, VA, 19 Feb. 1866, p. 2. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Accessed January 12, 2022. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1866-02-19/ed-1/seq-2/

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Arlington County, Arlington County, Virginia. Sanborn Map Company, 1936. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/sanborn08973_001/

Fairfax County GIS & Mapping Service. Historic Aerial Photographs. Fairfax County Government, Fairfax, VA. Accessed January 14, 2022. https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/maps/aerial-photography

The Louis Berger Group, Inc. “Bold, Rocky, and Picturesque” Archaeological Identification and Evaluation Study of Rock Creek Park, Volume I. 2008. http://npshistory.com/publications/rocr/aie-v1.pdf

Hartford Courant, Hartford, CT, November 19, 2015. Accessed January 14, 2022.

The rock formation that is known as Brandymore Castle was designated a local historic district by Arlington County in 1986. Following is Arlington County's announcement:

In Madison Manor Park near North Roosevelt Street and Four Mile Run.

Date: n/a

Historic Designation: Local Historic District, May 17, 1986

Current Use of Property: Passive Recreation

Brandymore Castle is a natural landmark, significant because it was used as a locating point to determine the boundaries of at least five early 18th-century Northern Neck proprietary land grants. Brandymore Castle was a recognizable landmark as a rock formation with a massive outcropping of quartz situated at the north end of Madison Manor Hill, above the point where Four Mile Run formed a loop prior to the construction of Interstate 66.

This rocky outcrop was named for its castle-like appearance. It was first described in 1724 by surveyor Charles Broadwater as “the Rock Stones called Brandymore Castle.”

The exact location of Brandymore was in dispute until 1973, when Robert Moxham, a geophysicist in the Isotope Geology Branch of the U.S. Geological Survey, presented research placing the landmark on Madison Manor Hill, rather than Minor Hill. A County historical marker formerly identified the site, but it was removed during the construction of Interstate 66 in the late 1970’s.

Although the residential development of Madison Manor surrounds the hill and construction of I-66 has altered the setting of the rock formation as seen in the early 18th century, the immediate area of the rock formation remains intact. Brandymore Castle is an important natural landmark that provides a link to settlement patterns in Arlington during the early 18th century.

SOURCE: https://projects.arlingtonva.us/projects/brandymore/

It’s a relatively easy walk up from the W&OD Trail to the limestone rock outcrop. In 1973, the Arlington Historical Society published this description of how the geologic formation (it is limestone, not quartz) got its name:

In 1649, Charles II, King of England, Scotland, and Ireland, granted seven Englishmen all the land between the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers as a proprietary colony - despite being in exile and not having the power to do so. The grant was known as the Northern Neck land grant as it encompassed 5,282,000 acres of Virginia’s Northern Neck. This land had previously been (and partially still inhabited by) the Monacan Indian Nation, the Doeg, the Mannahoac, and the Powhatan, among other groups, and had been transferred without their permission.

Surveyor Charles Broadwater had travelled from Surrey in England, to Virginia several times in the six years prior to finally settling in the area in 1716. He and his wife Elizabeth Semmes West had two children. He immediately became very involved with the community, building a wharf near Great Hunt Creek (now Alexandria) and becoming a vestryman for Truro parish (largely in southern Fairfax County.)

On January 15, 1724, Charles received one of the Northern Neck land grant parcels NN-A-113, a 151-acre tract straddling the line between Fairfax and what is now Arlington. This was only a small part of his land holdings; between 1724-1726 he owned 2,089 acres.

Land grant to Charles Broadwater with Brandymore Castle noted as a wayfinding marker, courtesy of the Library of Virginia, Virginia Land Office Patents and Grants, Grants A 1722-1726

Landowners were required to fulfill a number of requirements to ‘perfect’ or take complete claim of the grant, including paying taxes, surveying the property boundaries, and constructing a building. Virginia was still only minimally developed, with hundreds of acres with barely a sign of European presence, so memorable natural elements in the landscape were important wayfinders for surveyors and early settlers. The earliest named record of the quartz outcrop near the border between current City of Falls Church and Arlington is by Charles Broadwater himself, who described it in 1724.

The origin of the name is unknown- there is no Brandymore in Surrey, and Charles Broadwater made no reference to how he settled on the name, or who had named it before him. However, the name stuck not only in his notations, but also in official land records. Brandymore Castle went on to be mentioned in five other Northern Neck land grants as a key landmark in the earliest proprietary land surveys of Virginia.

In 1986, Arlington County’s Historical Affairs and Landmark Review Board (HALRB) recommended that the County Board designate Brandymore Castle as a local historic district to recognize its role in and representation of early settlement in Arlington.

The limestone outcrop has changed over the centuries as it has weathered almost 300 years since it was first seen by Charles Broadwater. It stands as a tangible reminder of the natural beauty that once dominated a rural landscape. This oft-forgotten stone outcrop was once a beacon for hundreds of acres of undisturbed forest.

In 2001 one of the larger stones was defaced by vandals. This required specialized cleaning with environmentally safe methods on the part of the Arlington County Parks Department. Because regular cleaning agents can be extremely harmful to the stone, and the runoff would have been toxic to the natural environment around it, the stone had to be sandblasted and then hand cleaned with water.

If you visit today, you’ll notice that even now one of the stones is noticeably brighter than the rest!

Photo taken 2001, Arlington County Historic Preservation Program

Open in Google Maps

References

Wise, Donald A. “Some Eighteenth Century Family Profiles, Part 1”, Arlington Historical Society Magazine, Vol. 6, No. 1, October 1977.

“About the Virginia Land Office Patents and Grants/Northern Neck Grant and Surveys”, Library of Virginia, accessed December 5, 2018 http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/opac/lonnabout.htm.

Moxam, Robert M., “The Re-Discovery of Brandymore Castle”, Arlington Historical Society Magazine, Vol. 5, No. 1, October 1973.

"Preservation Today: Rediscovering Arlington" is a partnership between the Arlington Public Library and the Arlington County Historic Preservation Program.

Preservation Today: Rediscovering Arlington

Stories from Arlington’s Historic Preservation Program

Arlington’s heritage is a diverse fabric, where people, places, and moments are knitted together into the physical and social landscape of the County.

Arlington County’s Historic Preservation Program is dedicated to protecting this heritage and inspiring placemaking by uncovering and recognizing all these elements in Arlington’s history.

To learn more about historic sites in Arlington, visit the Arlington County Historic Preservation Program.

SOURCE: https://library.arlingtonva.us/2019/04/11/rediscover- brandymore-castle/

The Historical Marker Database geolocates the Brandymore Castle historical marker and notes several other nearby landmarks.

Inscription.

This landmark was first described in 1724 by surveyor Charles Broadwater as "the rock stones called Brandymore Castle." Research in 1972 established that the natural formation matched the boundary descriptions on the 18th century land grands from Lord Fairfax to William Gunnel, James Going and Simon Pearson, George Harrison, John Carlye and John Dalton, and Captain Charles Broadwater. The origin of the name "Brandymore" is unknown, but this rocky outcrop resembles the collapsed battlements of an old castle with Four Mile Run serving as a moat.

Erected by Arlington County, Virginia.

Topics. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists:

A significant historical year for this entry is 1724.

Location. 38° 53.052′ N, 77° 9.154′ W. Marker is in Arlington, Virginia, in Arlington County. Marker can be reached from Custis Memorial Highway (Interstate 66), on the right when traveling east. The marker is best reached from the parking lot for East Falls Church Park, off North Roosevelt Street. The marker is along the

Washington & Old Dominion Railroad Trail Park, which runs next to the interstate at this point.

Marker is in this post office area: Arlington VA 22205, United States of America.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker.

Original Federal Boundary Stone, District of Columbia, Southwest 9 (approx. 0.4 miles away);

East Falls Church (approx. half a mile away);

Granite Acroterion (approx. 0.6 miles away);

East Falls Church Station (approx. 0.6 miles away);

Fairfax Chapel (approx. 0.6 miles away);

Presidential Visit to Falls Church, 1911 (approx. 0.7 miles away);

Pearson's Funeral Home (approx. 0.7 miles away);

Taylor’s Tavern (approx. 0.7 miles away).

Touch for a list and map of all markers in Arlington.

Credits. This page was last revised on June 16, 2016. It was originally submitted on June 6, 2008, by Craig Swain of Leesburg, Virginia. This page has been viewed 3,340 times since then and 183 times this year.

Adapted from: https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=8180